Never short of a slang word or three, Australians now have ‘enshittification,’ which has become their national dictionary’s Word of the Year. The Macquarie Dictionary’s previous winners of the accolade include ‘cancel culture’ (2019) and ‘milkshake duck’ (2017), the latter being a popular social media personality who’s later found to have a dark and reputation-damaging past.

The term enshittification was first coined by Corey Doctorow in 2022 in an essay on Amazon, and has spread to all corners of the internet as a term usually coming up in the context of conversations along the lines of ‘the internet isn’t what it used to be.’

Enshittification was explained at greater length a few months later by Doctorow. It means a three-phrase process that digital platforms go through over time, from initial launch to maturity.

Phase I: Platforms are developed and appeal to users, offering them something they want and find useful. Focus is on users.

Phase II: Platforms change so that they appeal to business customers. The experiences of their initial users deteriorate. Focus is on businesses.

Phase III: Business customers are forced to pay higher prices for a deteriorating service. Focus is on the platform’s profits and its shareholders.

Phase III usually takes place after the business users of a platform are committed financially to using it as part of their workflow. In some cases, companies have built their entire operating model on the platform, and so are utterly committed to it and would find it difficult to extract themselves. The initial users have either left for an alternative platform, or rarely use it.

As an example, the subject at the centre of the first attribution of the word, Amazon, began selling books, CDs, and DVDs online. It had an attractive delivery system in place to make the experience for users easy and cheap.

Since then, its online stores have long since lost any semblance of objectivity in its recommendations for users, preferring instead to present options from suppliers that offer Amazon the best deal to show highlight their goods, like paying for ‘sponsored’ positions in search results – an example of phase II. Users have reported difficulty in discerning what are clearly inferior products presented ahead of better articles in recommendations and searches. In either case, individual users’ needs are ignored in favour of business users (resellers and third-party vendors, in this case).

Some of Amazon’s policies moved early into the final stages of enshittification, phase III (abusing the business users of a platform). As far back as 2012, the company announced that items sold via affiliate links would pay less per sale, a trend that continues to this day. And despite damning evidence presented at national government level in the US [PDF] and elsewhere, independent retailers using Amazon claim its dominance even poses “a threat to [their] survival,” and only 11% of sellers describe their experiences using Amazon as successful [PDF].

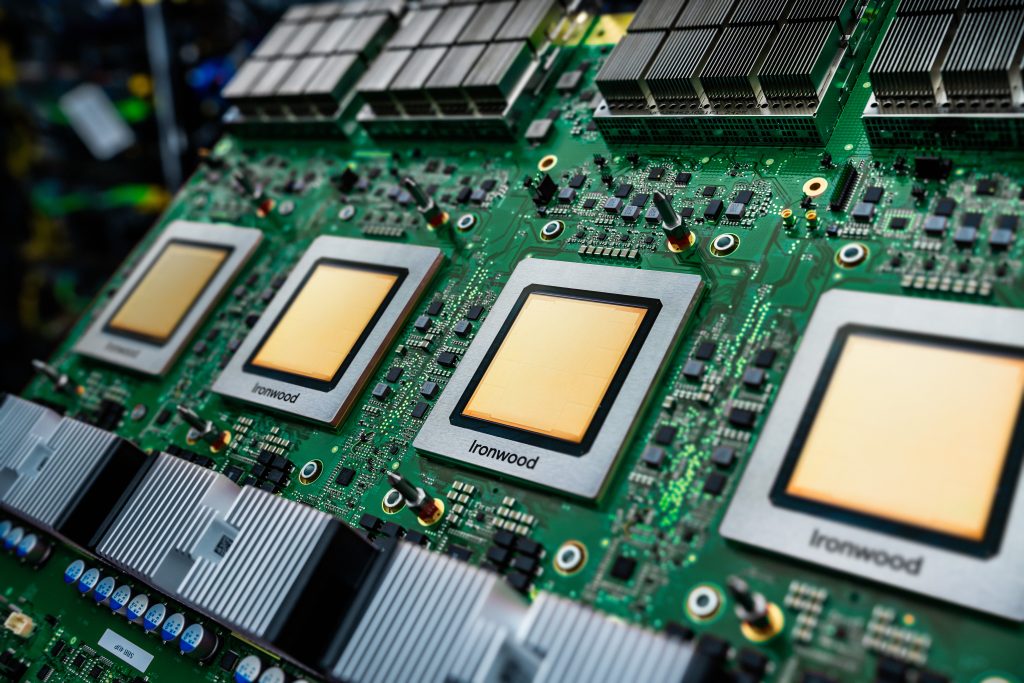

Venture capital, investment, and payback

The tendency of large technology platforms to deteriorate in terms of value to their users (individual and commercial) can be partly explained by the presence of venture capital, loaned early in the lifecycles of online platforms. Eventually, the company’s debts have to be repaid, which are on the whole by this stage, ‘owned’ by the eventual platform owners, the shareholders who bought into the platform.

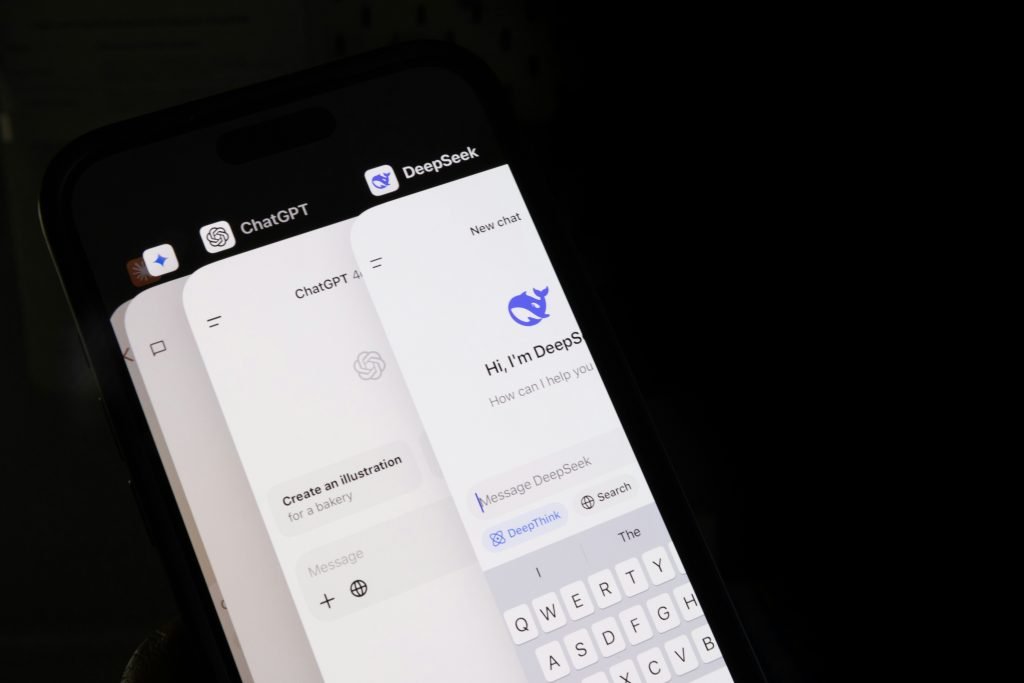

Doctorow has called for two general principles that users of digital platforms should insist on: the ability to exit from a platform (and take data out of it) if unhappy with the service, and the prioritisation by platforms of the user. In the case of a search engine, for example, that would be showing search results useful to the enquirer positioned above sponsored advertising. To that requirement, this author would add the demotion of un-requested AI-generated results being presented at all.

The author and activist who first coined the phrase enshittification is reportedly pleased that his word is gaining mainstream use. In an email to Gizmodo, he said: “If ten million people use the word colloquially, and 10 percent of them go look up what I have to say about it, that’s a million normies that I get a chance to radicalize.”

If radicalization (sic) means going into a subscription or contract with a digital platform armed with some pre-warning about what will happen, then organisations need to get radical.